Eat well – sleep well

- 7 May 2020

At some point most of us resolve to lose weight and adjust our diet. But before we set out on a new diet with […]

Against a towering sandstone bluff, early humans huddled together on a 30-centimetre deep mattress of reeds and rushes, covering themselves in bedding made from grasses and leafy plants. A “top sheet” of fragrant wild quince leaves drove away insects and gave the sleepers some relief from biting pests, though the material was sometimes burned for a more thorough cleaning.

Ever since then, the bed has remained at the centre of our homes and our domestic lives. The earliest beds were, naturally, made from locally-sourced materials. In the windswept Orkney islands of Scotland, wood was in short supply, so the Stone Age people of Skara Brae made all of their furniture, including beds, from slabs of rock2. Many of the 5000-year-old homes had two stone beds on either side of the hearth, the one on the right always larger, suggestion husband and wife slept in separate beds. The mattresses likely would have been constructed from bundles of bracken or heather, with animal skins as blankets.

Moving up in the world

Once humans began building furniture, it became clear that raising the bed off the cold ground could provide a much better night’s sleep. What’s more, a raised bed would let draughts – as well as insects, mice and other nightcrawlers – pass under the bed without disturbing the sleeper.

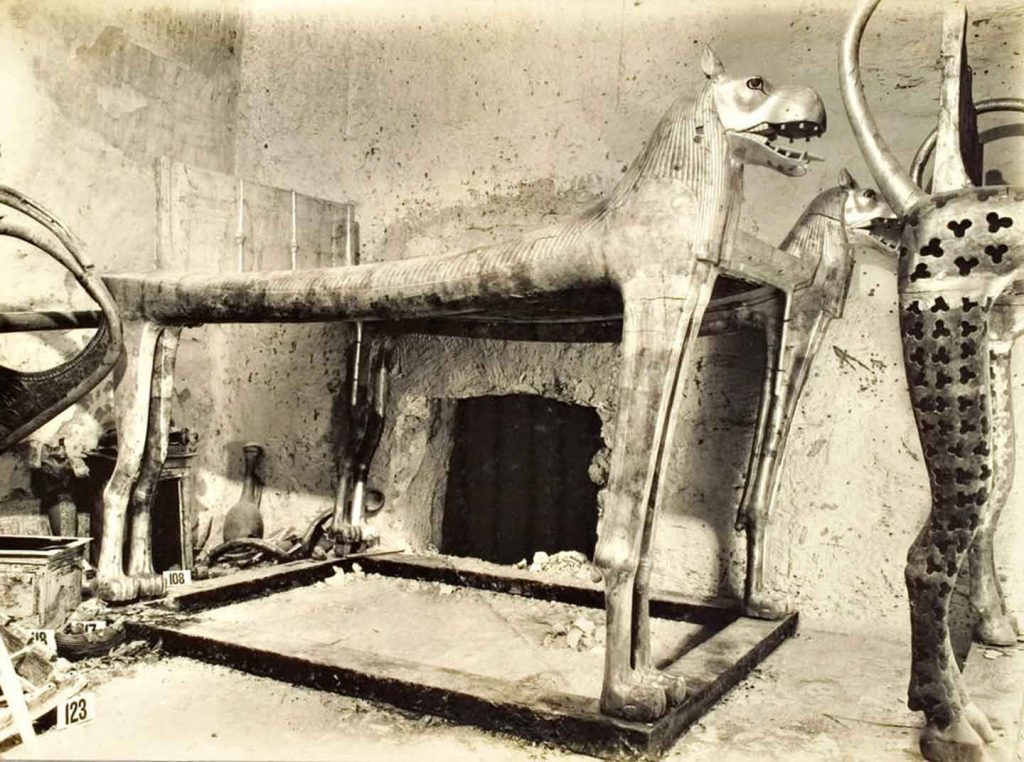

Artefacts recovered from Ancient Egypt’s burial chambers include beds fit for a Pharaoh. In the case of Ramses IX, the frame was carved from dark hardwood and fixed with nails of silver and gold. The bed perches on hoofed legs, entwined by cobras made from ebony and gold sheet3. Reeds, leather or linen straps would have been woven across this bedframe to provide a surface for the mattress to lie on.

Some Egyptians slept on an inclined bed4 with a footboard to stop the occupant sliding out the bottom in the night, while other beds offered a curved surface rather than a flat one. For a pillow, a simple block of wood sufficed. Bedrooms still hadn’t been invented, and less wealthy Egyptians probably slept on the roof of their building, on simpler frames or none at all. To keep warm on those cold desert nights, Egyptians could choose from blankets of woven reed, wool or linen, depending on their finances.

The Egyptians are not the only ones to have slept on bed frames sprung with cords. The Indian charpai follows the same basic design, a wooden frame strung with cotton rope. The Ancient Greeks, too, were fans of this model: the Odyssey describes its eponymous hero building an immovable nuptial bed from the stump of an olive tree, stretching a crimson hide across it5.

The Romans saw no reason to abandon the Greek design for raised beds, and those who could afford to constructed bedframes from maple, oak, beech or willow, fixed with brass nails, using a net of rope or leather cord to support the mattress stuffed with hair or straw. The supports were woven in such a way that sagging ropes can be pulled taut: thus the exhortation to “sleep tight”.

The exhortation “sleep tight” comes from the fact the supports were woven in such a way that sagging ropes could be pulled taut.

If you were showing off to your fellow Romans, you might use a metal thatch support in place of rope, and decorate your bed with gold, tortoiseshell, ivory, or other precious materials. And rather than stuff your mattress with straw or coarse wool, you might opt for soft feathers6. Curiously, the Romans built their beds high enough that they often needed steps or ladders to get in and out of them (perhaps the mice were bigger in Rome?).

Frescoes from the time show beds covered with decorated blankets7 and cushions, further evidence that as well as being status symbols, beds were made for public viewing. Romans had a variety of beds that were defined by their use: the lectus cubicularis for sleeping, a communal day bed for lounging and eating on called the lectus discubitorius, and even a deathbed, the lectus funebris, to transport the bodies to the pyre. The idea of a bed for sitting in led to the development of the headboard to lean against, which persists to this day.

Beds were also being raised on the other side of the Atlantic. When Christopher Columbus arrived in what is now Haiti at the close of the fifteenth century, the indigenous Taíno people introduced the Europeans to potatoes, tobacco, and nets that they slung between trees to sleep in, which they called hamacas. The hammock was an instant hit among sailors, who found them much more comfortable (and safe) to sleep in than fixed bunks, which often tipped the sleeper out in rough seas.

Hammocks took up less room on deck and weighed less, and offered more flexible use of space. England’s Royal Navy – which had been quartering its sailors in slung cloths prior to Columbus’s transatlantic voyage – hung them in the gun decks where they could be tidied away each morning. Hammocks remain popular in Central and South America, as well as among those sleeping rough, where the ground is not flat or dry enough to set up a bed.

Amid all these raised beds, the Japanese held out, preferring to sleep on cotton or seaweed filled futon cushions8 placed on the floor, aided by small wooden pillows9. Perhaps the Japanese had no need to raise their beds, given that the traditional wooden houses were already built off the ground, and the hard floors were already covered in soft tatami mats. Yet while Europeans were stuffing their mattresses with ever softer and more luxurious fillings, Japanese sleepers pursued a more ascetic repose. Today there are endless pages touting the benefits of sleeping on these thin, hard cushions, promising they will be easier on your back as well as your wallet.

Empires rose and fell, but people kept on sleeping, and the need for a good night’s rest continued to be a central concern for everyone. Advances in weaving technology led to the arrival of modern ticking around the fourteenth century: a heavy duty, tightly woven fabric that blended cotton, linen and hemp to provide structure to the mattress and keep the contents from poking through the material and scratching the sleeper10. Taking its name from the Germanic word teke meaning case, ticking fabric still covers mattresses to this day.

Entire families, as well as servants, courtiers, guests and

even strangers would share the room and the bed.

The bedroom was born.

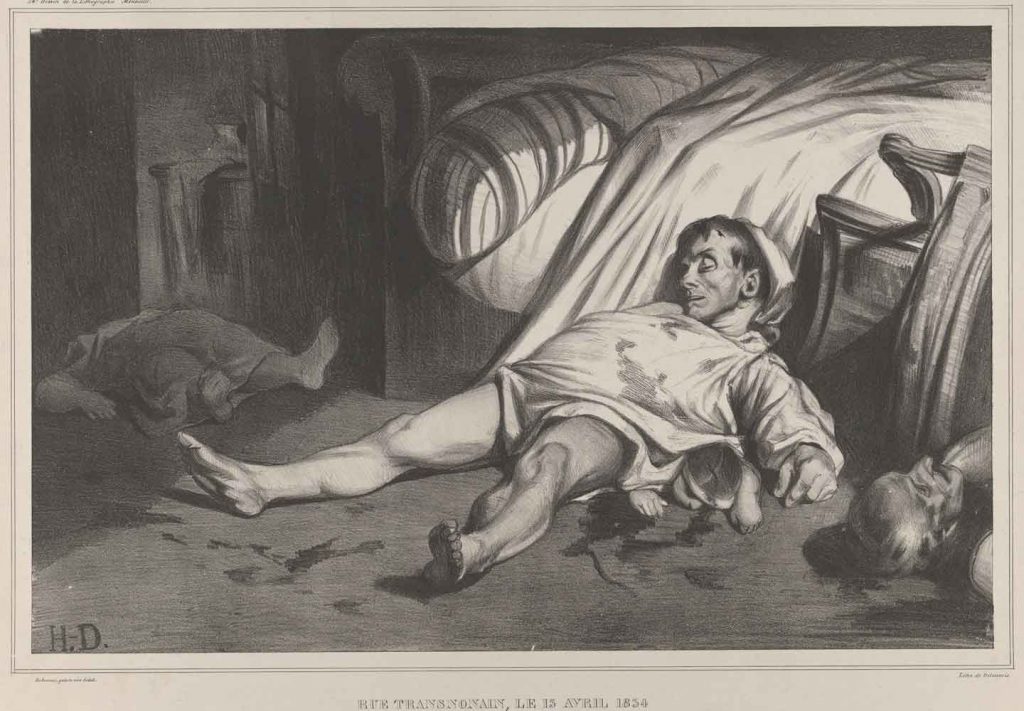

During the Middle Ages, it was common for all those living under one roof to gather in the same room to sleep, warmed by a crackling fire. At the centre of this room was a bed large enough to accommodate a family, and so the bedroom was born. Entire families, as well as servants, courtiers, guests and even strangers might share the room and even the bed11. Accounts from this time also talk of a second sleep: people went to bed, then rose for an hour or two in the middle of the night to read, write and socialise, before going back to bed for a longer sleep. It was the perfect era to be a night owl.

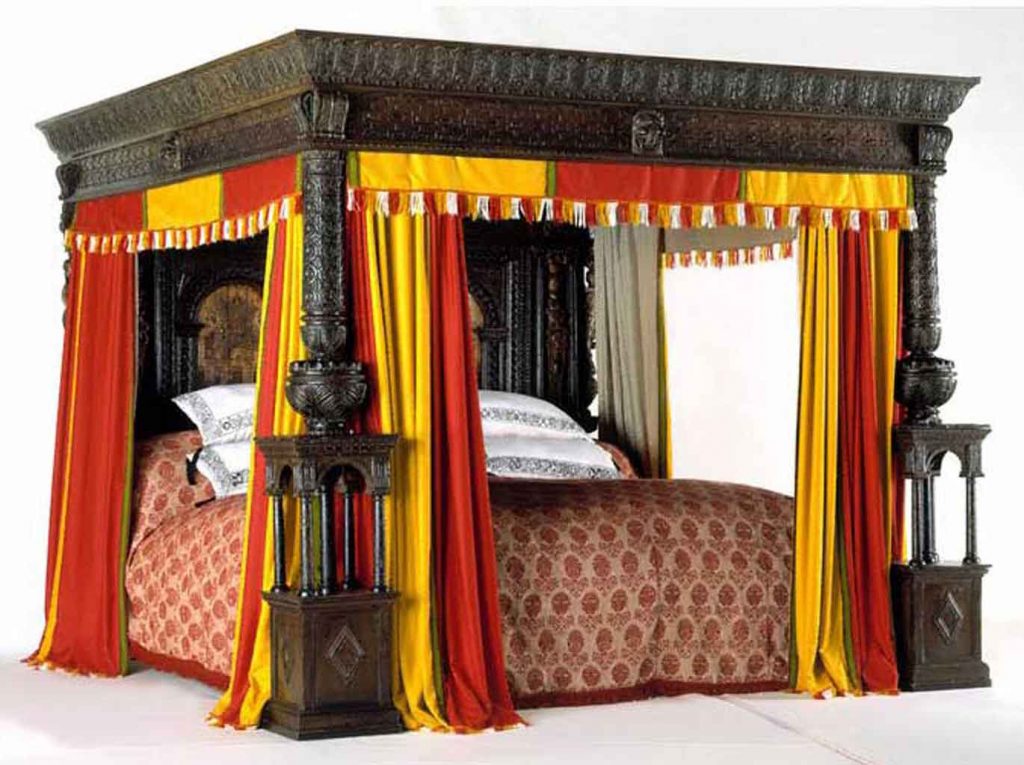

The size and grandeur of the bed naturally correlated with the wealth of the owner: a good bed was easily expensive enough to be considered an heirloom passed down through generations. The grandest of these was the four-poster bed. The pillars supported a roof called a tester, from which curtains could be draped to offer those inside protection from cold draughts – and prying eyes.

Royal beds were decorated with fine fabrics such as silk, damask and richly detailed brocade, and the mattresses stuffed with scented herbs. They served as a place to receive guests and conduct business. In medieval France, the lit de justice was a bed set up in parliament, on which the king reclined while he held court.

In 1590, the most famous bed in the world was constructed: England’s Great Bed of Ware. The colossal four poster bed, hewn from oak, measures over three metres on each side, and is reported to have once slept 26 butchers and their wives12. The bed served to draw travellers to the White Hart Inn – acting as a sort of early roadside attraction – and is even mentioned in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night. With space for so many additional guests, it probably wasn’t the best place for a good night’s sleep, but judging from the graffiti many occupants carved into the wooden frame, it was certainly something to tick off your medieval bucket list.

Communal sleeping declined in importance during the eighteenth century, and the bedroom became an increasingly private place to rest and escape the pressures of the outside world. Servants were given their own rooms to sleep in or expected to bed down in their corner of the manor: on piles of laundry in the steamy washroom, or on the kitchen floor, in front of the glowing hearth. Once stuffed with straw or horsehair, mattresses filled with cotton increased in popularity, as did metal bed frames.

With the advent of the industrial era, the world changed very rapidly, and so too did sleeping habits. Urbanisation led to a rise in workers living in their own homes and fuelled the division of people into individual sleeping spaces. For those who could afford the space, children were given their own rooms, with their parents in another. As Victorian prudence took hold, the notion of sharing a bed with anyone except your spouse became unthinkable13.

As Victorian prudence took hold, the notion of sharing a bed with anyone except your spouse became unthinkable.

As well as being morally unsavoury, sharing a bed was deemed unhygienic. The curtains which once enclosed bed spaces were likewise banished for trapping foul air around the sleeper, and bedrooms became cleaner and more open. Increasingly, the bed represented ideas not just of rest, but cleanliness, both physical and spiritual14.

Industrialised society was built around the factory clock, and the spread of electric light regimented the day into set hours for work, leisure and sleep. No longer did people spend the midnight hours praying or visiting neighbours between bouts of sleep: instead it was all taken at once. Yet hardworking factory workers might have something to look forward to at the end of a shift: a more comfortable bed.

In the mid-nineteenth century, coiled steel springs were arranged into rectangular arrays and sold as “boxed springs” aka the box-spring or divan. This was the first notable advance in bed frames since the knotted rope designs of ancient civilisations. Among the vanguards of this design was Dutch blacksmith Jan Auping, whose springy bases were sold as a “health mattress” to be topped with a kapok-stuffed cushion15 – further evidence of sleep as a good medicine.

Then in 1900, a Canadian engineer named James Marshall had the clever idea to embed the springs in the mattress itself, creating the pocketed spring mattress. The individually encased springs conformed to the sleeper’s body, providing an unparalleled level of comfort and support, so popular Marshall sold his design all over the world.

Just as pocket springs were taking the world by storm, a revolutionary type of comfort was achieved in 1929 with the invention of the foam latex mattress. Chemists working for Dunlop in Birmingham, UK, discovered that rubber could be whisked into a soft foam. Reportedly, lead engineer Edward Murphy used his wife’s cake mixer to create the first batch16. Dunlopillo cushions were soft, long-lasting, and did not need to be plumped or turned. They were an instant hit, but when Japanese forces captured rubber plantations in Southeast Asia during the second world war, the supply of latex was cut off – and so steel-sprung mattresses held on for many years.

Edward Murphy used his wife’s cake mixer to create the first batch of whipped soft foam. Dunlopillo cushions were soft, long-lasting, and did not need to be plumped.

By the middle of the twentieth century, the idea of the bed as a sacred space had reached its zenith, and married couples occupying separate beds was seen as a particularly modern choice – even if the hardy citizens of Skara Brae were doing it 5000 years earlier17. Yet even at the peak of this trend, double beds still outsold twin sets three-to-one18 in the UK.

In the early 1970s, Charles Hall invented the modern waterbed, hoping to revolutionise sleeping. The water-filled mattress could be warmed up to body temperature, and promised to conform to the sleeper’s outline. The rolling, wavy bed was a hit, and made up 20 per cent of US mattress sales by 1986.

Another material designed to conform to the human body was developed by NASA in the 1960s. The goal was to provide a cushion soft enough to keep pilots comfortable on long haul missions, while still being firm enough to offer protection in a crash. The technology was declassified in the 1980s, and the memory foam mattress soon followed.

Today, consumers can choose from a dizzying array of materials to sleep on: natural fabrics such as wool, cotton, horse hair, coconut and bamboo, synthetic alternatives such as latex and viscose, various gel, sponge and polyfoam fillers, and comfort technologies such as coils, innersprings and air pockets. Wherever humans have gone throughout history, the mattress has followed. The word itself is derived from the Arabic al-matrah, meaning “that which is thrown down”. Which is to say, soft furnishings cast on the ground to sleep on. Even today, when we speak of a mattress, we echo that soft, leaf-lined pit our ancestors built to sleep in 77,000 years ago.

Frank Swain is a science writer based in Barcelona, Spain, where his bed doubles as a work desk / where he shares his bed with his cat Chester.

Footnotes

1 Oldest Known Mattress Found; Slept Whole Family – National Geographic

2 Skara Brae – The Discovery and Excavation of Orkney’s finest Neolithic Settlement– Orkneyjar

3 Bed: ancient Egypt – British Museum

4 Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids – The Metropolitan Museum of Art (1999)

5 Book XXIII The Odyssey by Homer – MIT

6 A Smaller Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities by William Smith (1853) – Google Books

7 Ancient Rome by Peter Connolly (2001)

8 Atlas of Sleep Medicine by Lois E. Kran et al. (2010)

9 Manners and Customs of the Japanese in the Nineteenth Century Book by Philipp Franz von Siebold (1841)

10 Ticking History – Dreaming Global

11 A Day in a Medieval City by Chiara Frugoni (2005)

12 The Great Bed of Ware– V&A Museum

13 Worlds of Sleep by Lodewijk Brunt (2008)

14 A Cultural History of Twin Beds by Hilary Hinds (2019)

15 Worlds of Sleep by Lodewijk Brunt (2008)

16 About Dunlopillo

17 Together and Apart: Twin Beds, Domestic Hygiene and Modern Marriage, 1890–1945 by Hilary Hinds (2010)

18 A Cultural History of Twin Beds by Hilary Hinds (2019)

By submitting this form you agree to receive our newsletter and marketing offers from Owl + Lark.

© Owl + Lark Limited 2022

Winterman House, 11 Old’s Approach, Tolpits Lane, Watford, WD18 9QY | Company number 12398178